Painting and Buddhism are good pals. While wandering together through New York’s galleries and bars, Painting regularly ponders the difference between good and bad pictures – and Buddhism counters with old Tibetan words of wisdom on which Painting’s ambitions roll off like rain from the oil stains on the asphalt. When Chris Martin dispatches Painting and Buddhism through the streets of Chelsea, dirt crunches under their shoes. And while whimsically arguing about the essence of painting in Martin’s article »Buddhism, Landscape and the Absolute Truth about Abstract Painting« for The Brooklyn Rail, the smell of alcohol on their breath combines with the putrid sweet smell of nocturnal Manhattan.

Painting and Buddhism – just as abstraction and spirituality – appear in Martin’s article in addition to his work like two old friends who, unshaven and somewhat dishevelled, flee from colour-field painting’s precious surfaces and esoteric New Age murmurs into the next bar, to down the postmodern chic of the last preview party with a few beers. Martin is not an ironist. But the doubled solitary confinement of a spiritual art in the hallowed halls of the white cube on the one hand, and in the saccharine lotus esotericism on the other, is not for him. To be sure, he stands in the tradition of modern abstract art’s spiritual branch, whose saints, as canonised by our museums, range from Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Barnett Newman and many others up to and including Helmut Federle. But the further Martin’s work reaches, the more it extends over and above this canon, in fact takes it to very different social contexts to be discussed here.

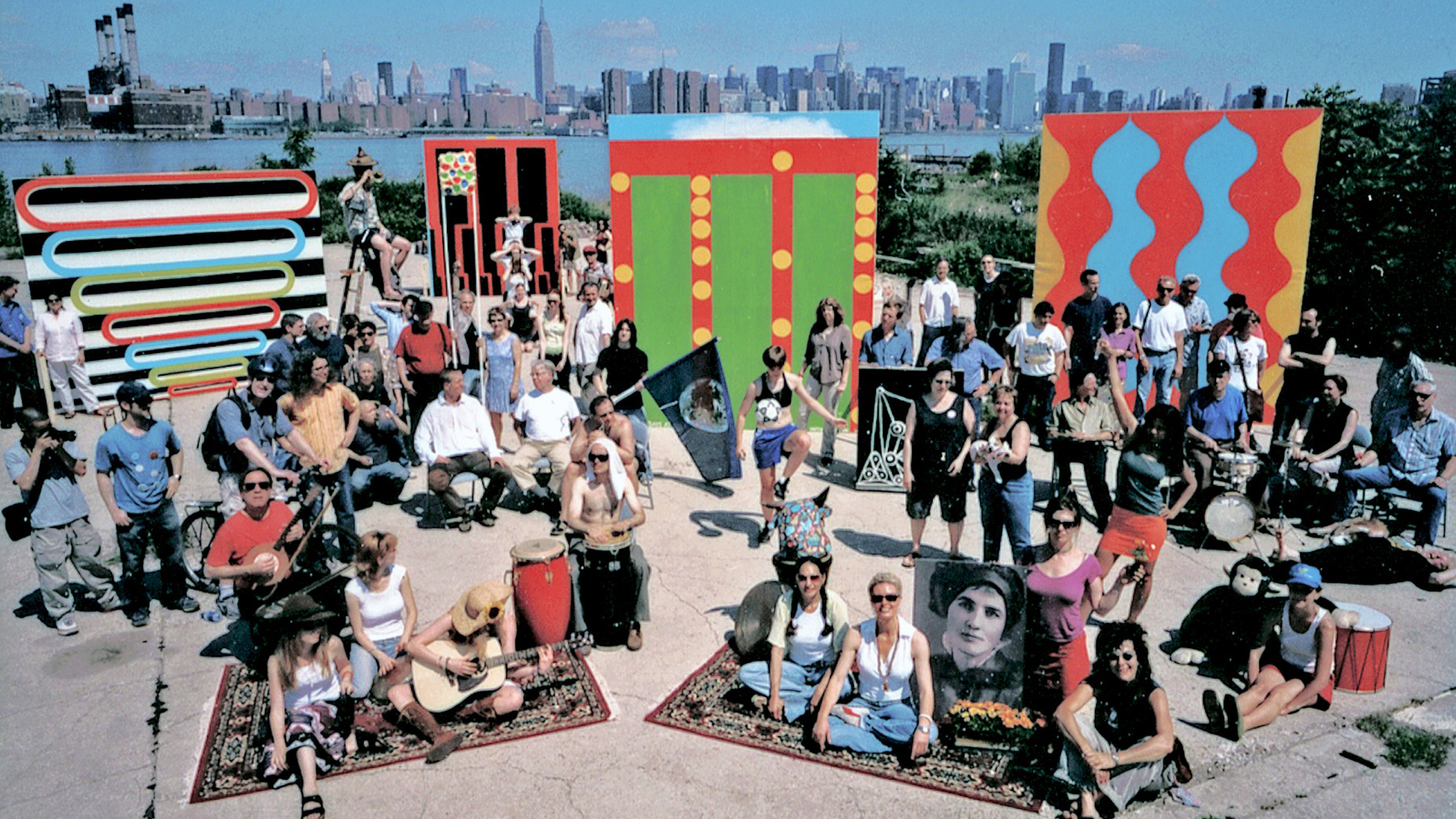

»Abstract painting is the dirt that catches the sun,« writes Martin and seeks the aesthetics of the sublime in this world, in the everyday, in popular culture, and in his neighbourhood on Graham Avenue in Brooklyn, where he moved his studio in 1984. Since the early 1990s he has regularly hung canvasses on the facades of buildings on the surrounding streets and leaves them there for weeks. In 2000 he painted a group of large black-light paintings for the Galapagos bar, adjusting it to the ultra-violet light of the night. For a 2005 exhibition poster, he took a photograph on the bank of the East River showing 50 friends gathered around the artist and four of his large-format paintings like a hippie community at a street fair. Particularly large canvasses are painted on the roof of his studio or outdoors on the pasture, where chickens strut across the fresh paint, and rain washes away one or the other picture before it even had the chance to dry. »If everything is futile anyway,« you hear Buddhism saying, »why bother tidying up?«

Where does this gesture come from that seems somewhat coquettishly relaxed at first glance; somewhat idiosyncratic, eclectic, and very literally romantic? What is Martin driving at? What is he offering us that deserves our attention and perhaps even our approval? What does his painting contribute to art history that makes it worthy of assuming a place in it? Why does he paint mushrooms? And what do they have to do with Buddhism? A first quick response: Chris Martin generously builds bridges between cultures that have long proven their peaceful coexistence in the everyday lives of many people, but which have an effect like oil and water on all those people who would prefer that their lives and the world (and art) were systematic – cate-gorised in compartments that ensure that everything is in its proper place. And of all places, he builds these bridges leading from an old consecrated plateau of Western sophistication, namely the abstraction that has long served the United States as a trademark of its rational and spiritual superiority over other ways of life and ideologies.

It is possible that in the process, he is not doing a service to some American identities. This explains why he has heretofore paid scant heed to the aesthetic canon of the (art)political mainstream. Even though, like few others, Martin has the capacity to reconsider one of the great ideological achievements of American history for the present day: the conviction that the solidarity of a person toward the body politic does not depend on his or her religious feelings. The fact that this conviction has fewer followers today than in past decades makes Martin’s oeuvre appear even more politically relevant.

Here, 1995–1996

For 12 years starting in 1992, Chris Martin worked as an art therapist with HIV-positive patients. Their dying is reflected in his series of Death Paintings. Here can be seen as the key work of this group. The drawing of a geometric cube lying on the horizon line guides the viewer’s attention into the depth like a window reveal situated in the middle of 12 square-meter monochromatic black ground. Martin makes programmatic use of one-point perspective, embodiment of the humanist turning point during the European Renaissance. But the fleeing lines in Martin’s painting open no window to a divinely ordained world inhabited by human beings. They describe an interior space in the middle of nothingness, a portal in the void. Here marks an imaginary space at the threshold between this world and the next, a narrow zone between us and death. Heremeans a spiritual place.

But where is this place, precisely? In answer to this question, Martin shows his renunciation, in terms of content, of the colour-field painting that his pictorial concept nevertheless seems to resemble at first glance – thus also of a guiding aesthetic paradigm of post-war modern art in the West. This renunciation is also evident in his use of one-point perspective, which is so firmly grounded in the pictorial culture of Christian art. Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, two major proponents of colour-field painting, rejected perspective space and saw immersing one’s sight in a colour space of painting as the gateway to a transcendental experience, which was closer to Jewish culture. Rothko’s subtle depths of colour and Newman’s strict monochromatic areas would directly dissolve the subject’s boundaries, its existence in the here and now before the canvas – also the artists’ reaction to the trauma of the Holocaust. To do so, it was necessary to blot out any and all attachment to the circumstances of the pictures’ environment. In opposition, Martin, who was essentially raised on Pop Art’s critique of abstraction’s purity requirement, virtually welcomed the profane, nearly lapidary character of his canvasses, literally covering them entirely with quick, course brushstrokes of paint. He does not suggest any exclusive dimension of experience that gives his picture surfaces an advantage of some sort over everyday objects as a result of whatever subtle materiality and, unlike Rothko and Newman, does not have to presuppose the »neutrality« of the white cube. As one commentator wrote, Martin’s pictures are as »daily as breakfast.« It is therefore by no means surprising that years after Here, he completely covered some canvasses with pieces of toast or with pillows.

And the horizon line that Martin drew under the central axis? It structures the canvas into a top and bottom, thus suggesting a landscape. In other Death Paintings, stars are additionally painted in the top third of the picture, underscoring the impression of a nocturne. Landscapes at night in fact run like a golden thread through Martin’s oeuvre, for example in a such major work from the 1980s as John Bill Haynes’ House(1989). The window motif and the view into the darkness can also be found here. A band of text traverses the composition, providing a concrete written localisation and point in time for the painting, and that would appear in many others. And particularly large-format pictures such as Lake (2000) were painted after Here. A night-time swim in a lake, the horizon line has moved far above the centre of the painting; the inner pictorial viewpoint is close to the surface of the water. The rising moon and a few stars are rhythmically reflected in the waves. The tranquil sublime grandeur of the experience of nature is transferred to the viewer standing before this nearly 11-meter canvas. The picture’s composition and colours – which still appear in the Death Paintings for the most part as conceptual graphic reductions – now agree with the impression of nature. In his vocabulary of forms, Martin approaches indigenous folk art while thematically taking up the »spiritual landscapes« of American Romantic art that is still so little known in Europe. Lake is deeply rooted in the experience of the North American landscape und in the traditions of its representation.

But with »spiritual landscapes«, a term has been mentioned that concludes the question concerning the spiritual location in Martin’s oeuvre for the time being. Here is not the place of the dissolution of the subject’s boundaries in pure abstraction. Here begins here, literally, in the experience and in the position of a body in space, bound to a specific point in time and to a geographic topography that will increasingly become a social topography over the course of his work. Here is a meditative state with open eyes firmly set on the horizon – and in the case of the Death Paintings – on death as well. Ethical or religious assumptions, of which the history of abstraction has seen many, are not applied in this case. For this alone a debt of gratitude is owed Chris Martin for remaining impervious to any and all religious concepts. And yet, perhaps because of this, he is able to integrate the most diverse spiritual traditions into his paintings in a positive eclectic manner. Those who wish to hold fast to religious notions and their institutionalisation will receive little pleasure from Martin’s pictures. But those who conversely welcome the secularisation of the modern world and nonetheless acknowledge that it has offered the spiritual needs of many people few alternatives other than the capitalist value and commodity fetishism will consider Martin’s position.Â

Staring into the sun, 2002

Two trips to India in 1983 and 2002 had a crucial influence on Chris Martin’s painting. He produced a larger group of paintings in 2002 that represent a turning point in his oeuvre. Martin now worked with clear, in part garish hues and colour contrasts, finding his way to stable, powerful compositions. Titles like Ganges Sunrise, Sunrise Asi Ghat Varanasi, High Noon at Manikarnika Ghat, and Staring Into The Sunallude to their motifs. Varanasi (Banaras), the city of the god Shiva, is considered Hinduism’s most sacred site. More than a million people come every day and throng to the »ghats,« the cremation sites on the steps leading down to the banks of the River Ganges. According to Hindus, the soul of whomever is cremated here is released from the endless cycle of reincarnation, and thus they entrust the ashes of the deceased to the river. Death is again the focus of this group of works. The images mark a moment at the threshold between life and death. The break of a new day, the rising sun is mirrored in the waves blackened by the ashes at a place that people hope has the power to keep them from returning for another earthly existence.

Staring Into The Sun (2002) exaggerates the reflection of the sunlight into a gaudy yellow and red orange, a colour effect that occurs after looking directly at the sun for a moment. »Staring into the sun – that’s what you’re never supposed to do,« says Chris Martin, meaning the injuries that the retina could otherwise sustain by doing so. Only by looking down can one see the sun, which is reflected in the water indirectly. Another picture with the same title varies the theme. Three sections of canvas measuring a total of ten meters in height and three meters wide that have been pushed together are folded into the space in such a way that two-thirds of the picture lies on the ground, blocking frontal access to the vertical upper portion (Staring Into The Sun, 2002). Its top edge consists of a sunny yellow beam. Blue colour fields of various widths run underneath over a red background that tapers off in three stages toward the lower or front edge of the work.

The three panels address the tiering of the funeral processions and the masses of pilgrims pushing their ways through the city’s narrow streets toward the cremation sites, where the funeral pyres are located. But the composition also resembles a schematic depiction of the retina, the arrangement of rod and cone cells that process the arriving light – or are scorched when they receive too much of it. In the process, Staring Into The Sun interleaves in a remarkable way the physis of visual perception with the topography of the Manikarnika Ghat and thus the finiteness of the body with the finiteness of sight.

Incidentally, reproductions are pasted onto the lower edge of a second version of this three-part painting from 2011, including a picture of Amy Winehouse, who died the same year. Chris Martin dedicated a variation of the motif painted on a single canvas, High Noon at Manikarnika Ghat(2002–2003), to his friend and artist colleague Frank Moore. Moore was an AIDS activist who developed the red solidarity ribbon in 1991 with the Visual AIDS group. He died in 2002. High Noon… is thus turned into a requiem. The dedication is at the bottom right.

Dance, 2006–2008

Text elements, usually brief phrases from sentences, can be found in Martin’s work since the late 1980s. The first dedication of a picture I am aware of dates from 1996, Homage to Alfred and Bill (1982–1996). Martin is referring here to Alfred Jensen, an Abstract Expressionist painter who is less well known in Europe, and the New York painter Bill Jensen. But Martin previously seemed to still be at odds with his forebears – and with himself as well. In an earlier star picture (the seven-pointed star will later become one of Martin’s most popular motifs) entitled I Am Not… (1988–1992) he distances himself from icons of abstraction: »I am not Hilma af Klint,« »I am not Julian« (Schnabel), »I am not Alfred Jensen.« But also: »I am not Chris,« »I am not I.« The sentences are wedged onto a sky-blue background that visually opens up behind a canvas with a star-shape laceration that has been primed in black and sprinkled with gold confetti. But the »I« at the beginning of every sentence paradoxically and almost emblematically confirms, in the middle of the picture, the authorship of the person who is distancing himself. Identity and the ego might be negligible and overcome, as Buddhism aspires to, but the author’s »speaker’s position« remains initially in place.Â

The distancing from his heroes was later thrown into reverse. From 1996 to the present, Homage to Alfred and Bill was followed by uncounted inscriptions with which Martin pays his respects to colleagues from the world of painting and especially music; some of them famous, others far from the mainstream. Some, like Frank Moore, Michael Jackson, or James Brown, were occasioned by their deaths. Especially beautiful is a series of four small pictures that are all collaged with a pin-up girl greeting Alfred Jensen: Good Morning Alfred Jensen, Good Morning! (2005–2007). Good Evening Alfred Jensen, Good Evening! (2007). With his homage practice, Martin breaks through the competiveness nature and innovative thinking so typical of contemporary art. Here, too, he distances himself from modernist doctrines. He does not seem interested in originality or authenticity, but rather in extensive nets of inner and outer pictorial contexts that he throws out ever more generously. In the process, he continually incorporates new cultural, social, and political themes by means of references supplemented by collage techniques. His store of material is also growing, becoming lavish and scurrilous on occasion.

Martin’s homage practice reached its preliminary peak in Dance (2006–2008), as did his networking of diverse cultural contexts. Nine names are now placed in a row at the foot of the canvas, which is 3.4 meters high and 6.1 meters wide. Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Kool Moe Dee, and other 1970s pioneers and eighties icons of hip-hop and rap comprise the entire base of the image. They popularised the urban ghetto recitative, invented DJing and sampling – postmodern cultural techniques. The row of names also includes the Swedish painter, spiritualist, and anthroposophist Hilma af Klint and Alfred Jensen again … in addition to his lesser-known contemporaries Paul Feeley and Myron Stout. Martin’s large-scale composition places this multiple dedication against the backdrop of a social frame of reference. A portrait of each of the cited protagonists is additionally pasted onto the left edge of the picture like a small devotional image. Some of the people are allocated a collaged object: (plastic) marijuana leaves, coins, and dollar bills, vinyl records, newspaper articles, feathers, and pills. Alfred Jensen is given a shell. A banana peel has also been stapled to the canvas and painted black – a salutation to Andy Warhol and Pop Art that Martin has repeated on numerous canvasses.

One could think here of voodoo practices or summoning the dead with objects from their possession. While the title Dance and the buoyant vocabulary of forms indicate an homage to Henri Matisse – whose famous equally large-format painting La Danse(1909/1910) depicts five joyously moving women and was also painted as a sort of twin to La Musique (1910) – Martin’s painting appears as a dance of death, particularly in the context of his work. All the cited painters are deceased. The musicians, on the other hand, are still living. Matisse’s painting is pioneering in formal terms for its reduction down to three colours, with which the interior forms are filled in almost monochromatically. Martin employs the same formal principle. Six sweeping, regularly curved, completely white forms that, seen anthropomorphically, could doubtlessly recall gyrating hips, are encompassed within a monochromatic black field. Their edges are outlined in red, blue, and yellow. In the viewer’s perception, however, the forms seem to rest less on the dark ground than behind it, as if the canvas primed in black and opened six-fold in generous sweeps offers a glimpse of a white light space behind it, whose dimensions remain indeterminable.

Martin’s canvas again functions as a threshold between a worldly, in this case particularly socially and culturally definable place, and an intangible dimension that can in turn be characterised as spiritual. With their pointy ends, the white compartments of form are fitted in between the top and bottom edges of the work like Tibetan prayer wheels in their shrine. That such wheels, when turned, spin on their own axes like the row of dancers in Matisse’s painting, reaffirms the comparison between the pictures. But especially the lower base of Martin’s winding forms has been given much significance, while in Dance, as well as in all comparable paintings, the upper edge of the picture assists in containing the composition but is itself never addressed. A »top« – virtually required by Christian iconography and constantly exposed both symbolically and compositionally – does not exist in Martin’s work. To the extent that his compositions have a formal and energetic base, it is at the bottom, on the ground and absolutely in the dirt, which, as Chris Martin and the title of this

essay says, captures the sun.

Untitled, 2005

Pictures with such pulsating forms as in Dance form the largest and most reproduced group of works in Chris Martin’s oeuvre. With very few deviations, Untitledfrom 1988 already follows the same compositional principles. I wish to discuss this group in more detail because numerous individual examples enable a further analogy that is in turn not unfamiliar to Buddhism and closely affiliated especially with Tantric practice. As an example, I would like to discuss a small painting on cardboard, Untitled (2005).

Three forms simultaneously wind their way upward here from the lower edge of the picture, standing out black against a fiery red background. They extend up like flickering tongues of flame, each of them surrounding a different number of more or less white dots: five at the left, fourteen in the middle and seven at the right. Against the backdrop of Martin’s reception of Buddhism, it makes sense to link this energetic picture to Kundalini power. Tantric writings use the Sanskrit term Kundalini to describe the potential in the human being that comes closest to the energy of the earth, the material, and rests like a coiled snake at the base of the spine in the lowest chakra. The most elementary of all human forces can be awakened from there through yoga practices, meditation, and Tantric sexuality, like a fire that climbs up the spine and breaks through one chakra after the other (the white dots in Martin’s picture) to ultimately combine via the crown chakra at the top of the head with the cosmic, spiritual energy – which corresponds to the state of spiritual transformation, and enlightenment.

Not only in Indian Tantra but in Europe as well, a rising snake is one of the oldest symbols of life-giving force. Since Classical antiquity, it can been found as the symbol of medicine and pharmacology in the rod of Asclepius, and even in Gustav Klimt’s famed painting The Medicine (1900–1907), a golden snake uncoils in the same way from the base of the spine as in classic Tantric representations. Even in the Old Testament, God sent out fiery serpents against the people of Israel to punish their sins with its bite, which Moses in turn healed with the »brazen serpent« of enlightenment.

The fact that Martin, as described above, compositionally always leaves this moment of enlightenment blank underscores the fact that he does not proceed from any fixed spiritual principle, much less from concrete religious concepts which he would care enough about to represent. Admittedly, Untitled depicts the row of the chakras and their connections to each other in a virtually schematic manner by means of the snake or flame-like form at the left. (However, the first chakra is identical to the lower edge of the picture, the seventh with the upper edge – which the white line that only extends from the first to the sixth chakra does not break through and thus fails to overcome its connection to the material world, symbolised by a horizon line.) At the same time, the arrangement of the white dots in the two black forms further to the right reveals an almost ironic handling of the energy metaphor, to the extent that they make a particularly uncoordinated bubbling impression (and playfully overstep the horizon in the process!).

This brings us to Martin’s mushroom pictures. The earliest I know of dates to 1980 (Psilocybin). The motif still recurs regularly in Martin’s work today. Like the Kundalini snake, Martin’s mushrooms always stand on the lower edge of the picture, growing completely from the ground, as expected. As in Untitled, five orange red dots run up the stem of a mushroom to its cap in Mushrooms (2004–2008). Airily sprayed, white spots are distributed above like spores in a landscape. Another group of mushrooms is connected with an rhizomatic array of lines. Variously coloured dots bead and leap across the whole picture, and titles like Psilocybin leave no doubt about what kind of mushrooms are involved and where the shimmering impression of perception comes from. After all, its active ingredient is greatly heightening the experience of lights, colours, and contrasts and causing them to vibrate. As with LSD, the boundaries of consciousness seem dissolved. And like in Tantra, the self merges with its surroundings.

And if alchemistic symbolism has always assumed a central role in Martin’s work (numerology, anagrams, colour theory), it likewise alludes to alchemistic knowledge of the psychological effects of chemical substances and thus optimally suited to Martin’s apparent interest in mind-expanding drugs. Enlightenment as a trip. Mushrooms grow as high as trees in Big Glitter Painting (2009–2010) and shine, together with a cloud, neon yellow and orange against a night sky that glistens like cocaine powder. The »spiritual landscapes« motif is repeated here this time in the psychedelic merger of nature and the psyche, of the inner and outer landscape.

Ain’t it funky, 2003–2010

Ever since the horizon line was programmatically introduced in Here in 1986, it has established different perspectives of sight as well as of meaning. The horizon lines lay higher in the picture at times, at other times lower, but over the years they are largely located at the lower edge of the picture where as painted lines they provide a grip on reality in the shape of mushrooms, Kundalini snakes, and other compositions. As could be seen in Dance, they often place Martin’s paintings firmly on the feet of concrete cultural and social references that the artist feels close to, thinks about, or admires. He integrates them into the energetic context his pictures invoke with an unconventional, thoroughly profane magic.

References to music have dramatically increased in Martin’s work since 2006. The artist has said that James Brown’s death moved him in a way that even he found surprising. Martin grew up in Washington, D.C. as the child of an elitist white family in a Georgetown neighbourhood that now has so many alarm systems and security patrols that Martin describes it as particularly dangerous for that very reason. The traditionally strong black soul and funk culture in Washington meant that the young Martin could broaden his middle-class horizon, and the social emancipatory movements of rap and hip-hop became an alternative culture to his own heritage. In Rev. Al In Mourning (2006–2007), a newspaper clipping surrounded by white radiates from the middle of a canvas that has been coarsely painted in black. The clipping shows James Brown and the civil rights activist Reverend Al Sharpton leaving the White House in 1982. Together they wanted to convince President Ronald Reagan to declare Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday. Reverend Al wears black mourning clothes.

Martin has dedicated numerous pictures to James Brown since 2006, one of the most beautiful of which is Farewell Godfather of Soul… (2007). Reproduced twice from an album cover, Brown’s face, with a lightning bolt on his chest, is submerged in the depths of a black mass of oil paint, seconded by two delicate clouds on a narrow strip of blue sky. The fusion of spiritual symbolism and political themes is likewise explicit in Motown Music and the Astral Plane (2007–2008). Motown, the legendary Detroit album label, is considered the epitome of black emancipation through music. Two-thirds of the canvas has been covered with seven records by James Brown and Michael Jackson. Shimmering colourful lines with which, like in Mushrooms, the LPs are connected rhizomatically, veer toward a book under plastic foil at the top of the picture, which bears the title The Astral Plane. First published in 1895, the book’s author Charles Webster Leadbeater provides an introduction to theosophical thought that he, openly racist, regards accessible only to whites. Brown and Jackson are bundling their energy in order, so it seems, to banish this book and shoot it into orbit beyond the edge of the picture.

In Ain’t It Funky (2003–2010) – the title quotes James Brown’s 1970 album of the same name – connecting lines can be found between seven LPs. But these are supplemented by collaged pictures of

ritual sites, such as temples, and ritual acts. Reproductions of antique vases, a forest fire, a post-Cubist painting by Pablo Picasso (Three Musicians, 1921) and other such things can be seen on the edge of the picture. These reference pictures bulge on all sides from the edge of the canvas on their dramatically coloured underpainting, like a curtain toward the centre of the picture primed in black, making it appear like a theatrically staged scene. Tilted from the vertical to the horizontal, the canvas could be turned at any time into a dance floor on which the individual steps are predetermined, as in a ritual choreography. While the horizon line at the bottom is still present, Martin encompasses the energetic constellation in the middle with a no less complex subplot that circulates around the whole picture. In formal terms, the pictorial occurrence is excessive, the contrasts are hard, the brushstrokes coarse.

Based on West African traditions, James Brown’s funk music was in fact conceived with ecstatic, ritualistic dance experiences in mind. This often not only blurred the boundary between the auditorium and stage but also suspended corporeal perception in the flow of the music, animating a rhythmic merger of the self with its exterior. In Ain’t It Funky, Martin again very unmistakably underscores his pursuit of spiritual dynamics amidst cultural practices, objects, and symbols from diverse provenances. His pictures bind them together without hierarchies and amidst a social world that his painting feels beholden to, sometimes devoutly, sometimes solidarily, sometimes critically. He recently intensely seized on the art of the so-called self-taught artists from the southern United States, who are – less politically correctly – also called outsider artists. They live on the outskirts of America’s affluent society and with their rubbish make sculptures and pictures that approach African sculpture and cult objects. Martin attaches greater significance to that which is dismissed as »folklore« by the upper echelon of aesthetics than to the canonised celebrations of so-called high culture.

The transitory nature of the moment, of the body, of identity, the fleetingness of existence at the threshold of death, the nothingness of the material, are the great themes in Martin’s oeuvre. But for me, the most important thing is that he never complains about this finiteness, affirming it instead. To be sure, this occurs more reverentially in his early works than in his later paintings in which the respect for the thematic is not lost, but comprehended less generally and especially increasingly less abstract. I have chosen the term »spiritual abstraction« for the title of this essay, and by this I primarily mean the term for a genre of painting that since Hilma af Klint has devoted itself to the representation of metaphysical contents with non-representational means. The fact is – and that is what I am trying to demonstrate – that Martin’s paintings are highly grounded in the physis, in nature, sometimes with almost comic-like figurativeness, and they have the great advantage of not subjugating themselves to any metaphysical concept. They stand with both feet planted firmly on the social reality of their author who, despite being the subject of his work, hardly brings himself into play.

In Martin’s art, spirituality first and foremost has an empathic, in fact solidary character. In 2008, Chris Martin completed a picture that bears an inscription on the lower edge reading »A painting for the protection of Amy Winehouse« (For Amy Winehouse, 2004–2008). Martin draped a protective wall made out Kleenex tissues/fabric around a portrait of the singer who suffered from alcohol and drug addiction, encircling it with goggle eyes symbolising the public’s greedy glances. He pasted a candy cane for her onto the picture. After Winehouse’s death in 2011, it appears like a funerary object.