A broken love means most to the one who walks away from it – because the leaver is so profoundly invested in the connection that he or she tries to influence and mold it until the very end. Severing the ties to another human being gives that bond a final form. Breaking up as the last gesture of a love? I’m not sure how much there is to this logic. But it rings true of many artists who broke up with art. Only an artist who is deeply in love with her art can be wracked by such passionate doubts about it even to the point of despair that she finds serious motives to leave it behind or at least put her reservations into practice. This was the point of departure for Gestures of Disappearance.

To contemporary readers, “in love with art” may sound like a romantic cliché, but what the four artists in this exhibition have in common is a core drive that is quintessentially romantic: the yearning for a fusion of art and life so expansive and so complete that it encompasses everything in a passionate embrace—the whole subject, the whole body, and indeed reality in all its vastness. Looking back after thirteen years (and several loves and break-ups of my own), it seems to me that Ader, Burden, Cravan, and Lozano had so completely fallen for a vision that their work inevitably came to be about its hopeless impracticality; the impossible quest to devise a realistic future for it.

Their excessive utopian designs, shattered by reality, made them spiteful and sometimes bitter. In today’s perspective, all four look like childish rebels who set out in inflatable dinghies to conquer the impossible because they thought it was possible—and had to watch as their hopes deflated. Their experience arouses our sympathy, it lets us relate to them as human beings, but it also makes them representative characters of their era. As I have argued in General Strike, tendencies urging a withdrawal from art were especially prevalent in the 1910s and again after 1968, times of profound social transformation. Whenever humans have collectively risen to reach for a grand and feasible vision, they have always landed hard. Not all passionate utopians have survived the impact.

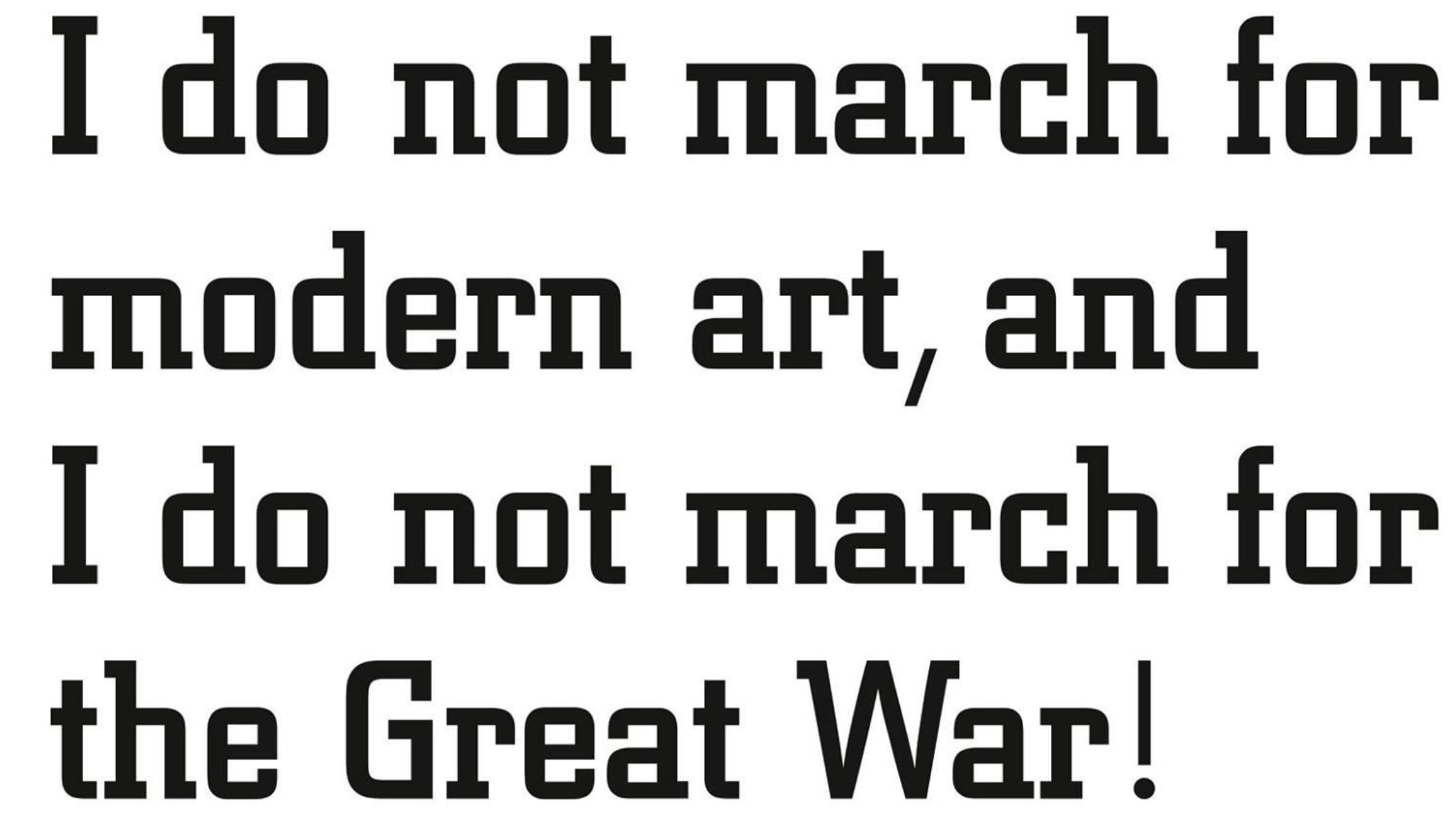

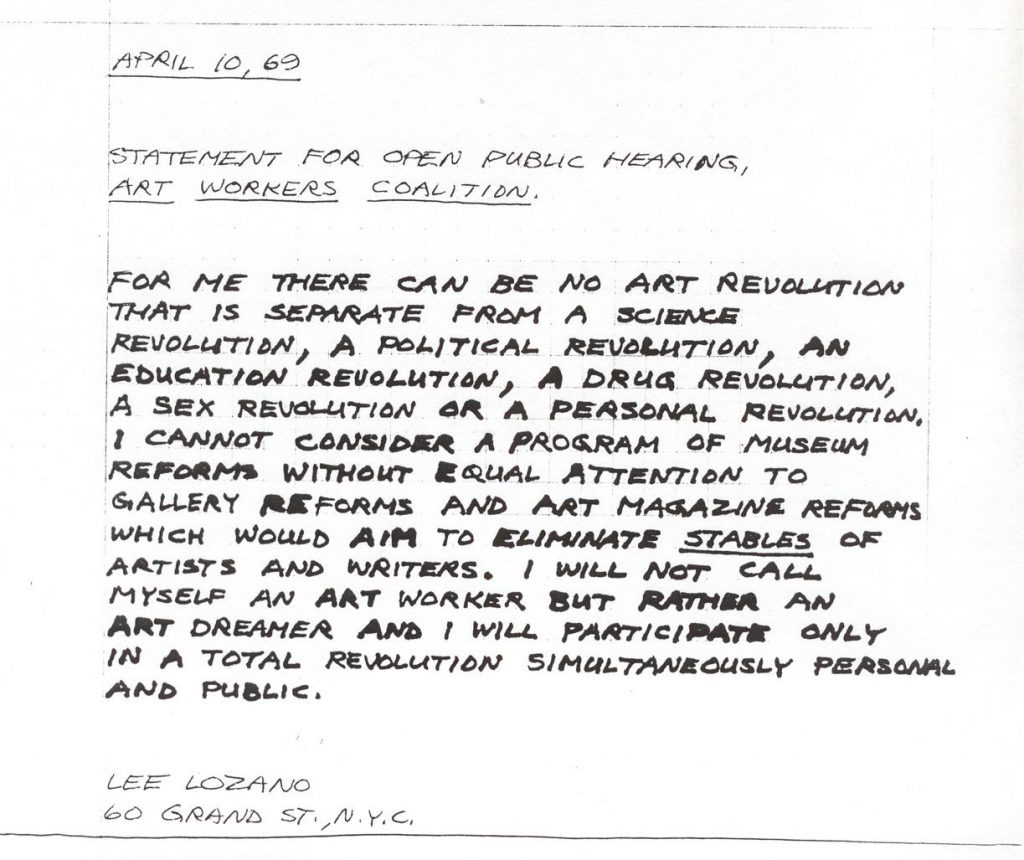

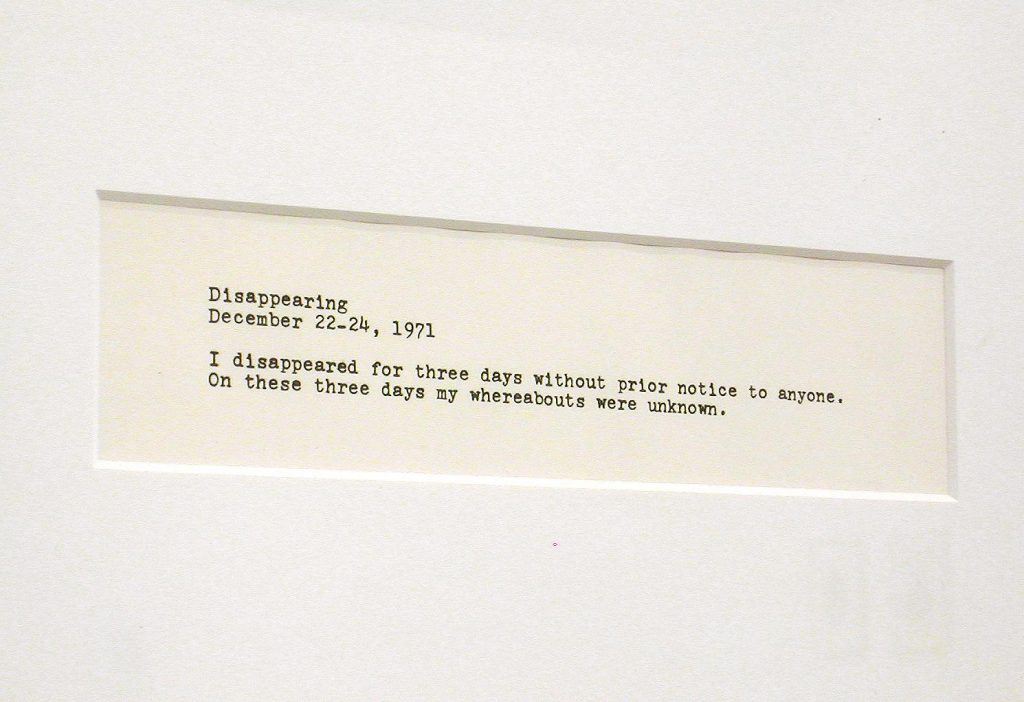

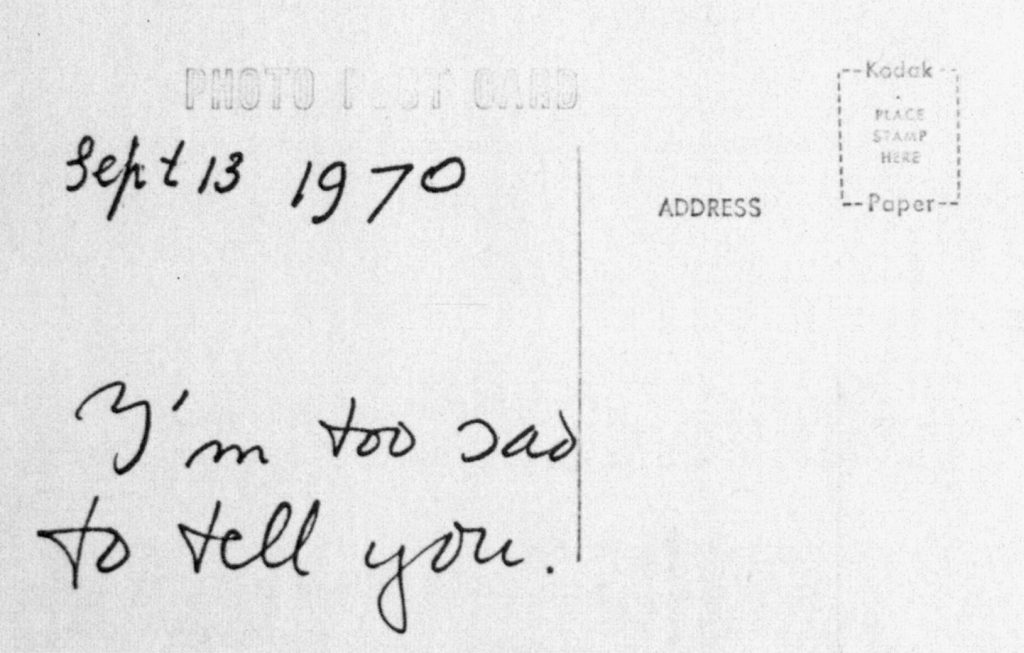

The urge to be free and break through barriers that propelled the swashbuckling poet and amateur boxer Arthur Cravan through the early twentieth century was not only broken by World War I; like Lee Lozano’s aspirations, it also collided with the narrow-mindedness and timidity of some avant-garde circles. Cravan flew high and fell; one of the first to crash into the limits of the modern rhetoric of self-determination. In 1969, Lee Lozano’s fascination with a “total revolution” of all domains of life gave way to an acerbic frustration with the vanities of the art world that eventually led her to leave art behind. She was also manifestly disappointed with the feminist movement, so much so that she refused to speak to women for three decades. Bas Jan Ader fell silent in his own way in the early 1970s; like a monk by the sea, he looked out over the void that was left after the bond between the subject’s inward self and its expression in language, its resonance in the outside world, had snapped. Chris Burden homed in on the same problem, and like Ader, he threw himself, his body, his existence into the balance in order to resurvey what was left of the freedom of art as a rebellious way of life beyond the well-rehearsed roles the art world afforded him.

The results were sobering: images, metaphors, and lived moments of loneliness and isolation, of rage and sadness. What the gestures of disappearance bury is nothing less than an emancipatory model of the role and behavior of an artist; the belief that the individual’s artistic practice can be sustainable and effective under the given social conditions. The exhibition’s four protagonists drew different conclusions from the loss of a horizon they would fain have set sail for. What united them is that they chose, for a brief moment, to perform gestures in which the fading of their emphatic belief in the artist’s role found clear articulation. The resulting eminent works made it possible to put these gestures on display in an exhibition identifying the positions of their authors amid the tumble of two of the twentieth century’s crucial transformative periods. In 2002, as we looked back on the tendencies in 1990s institutional critique, Cravan and Lozano in particular seemed to me to exemplify what was perhaps the most radical form of institutional critique one can imagine: closing the door for good on art as a viable option.

Gestures of Disappearance was conceived as a prologue, the pilot show to a series of texts and exhibitions about the decision to drop out of art. The idea was born in 2001 at one of those moments when I wasn’t too confident whether I still believed in the power of contemporary art to influence society. I was twenty-eight, with a teaching appointment at the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, and unsure about my options. I asked myself whether dropping out and trying to chart a different path might be the better choice, and I came to the realization that many others must have asked themselves the same question before me. In each generation, artists—and not only artists—must have wondered again and again whether to keep going or put down the brush, pencil, or camera. How did they decide, and why? What did that say about their trust, or distrust, in the potential of art in their time? There had to have been an entire history of a hidden movement of artists who criticized the social conditions constraining their practice—and its ability to affect those social conditions in turn—going so far as to break from art altogether.

When I started researching the subject, my initial question turned out to be a blank area—indeed, a blind spot—on the maps of theory production and the historiography of art. The deliberate abandonment of an artistic practice, the decision to shed the artist’s role, the withdrawal from the art world: no one, it seemed to me at the time, had seriously looked into or even thought through these things. So Gestures of Disappearance marked the beginning of a project I pursued over the course of several years, trying to close that gap (see General Strike, 2011). I never produced a second exhibition, however, because that would have seemed to me to run counter to the core issue. The act of dropping out of art as such cannot be put on display, and in the exceptional instances where it can—because we can identify works and documents that make the threshold situation of a gradual or sudden renunciation of all involvement in the art field tangible—the point of the whole enterprise would remain questionable. Why should I as a curator try to capitalize on it by putting together a spectacular display of artists’ letters of resignation? I had done something of the sort with Lozano and Cravan, but, although few people knew about them thirteen years ago, the art-historical literature had already taken note of their lives, albeit in incomplete accounts.

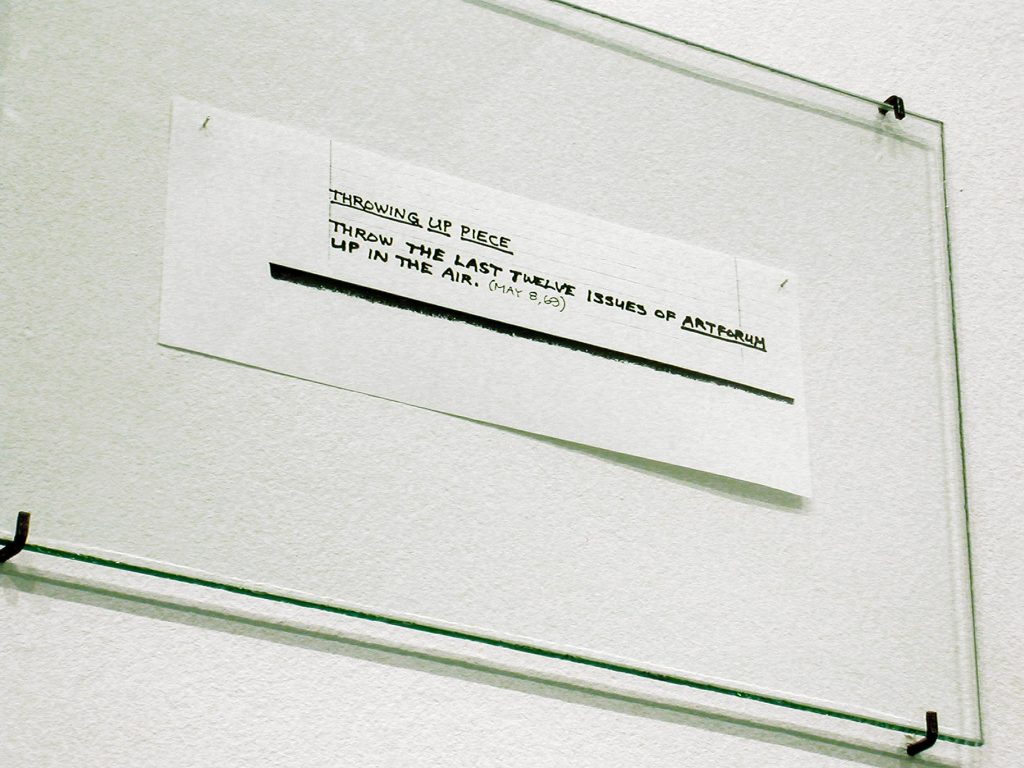

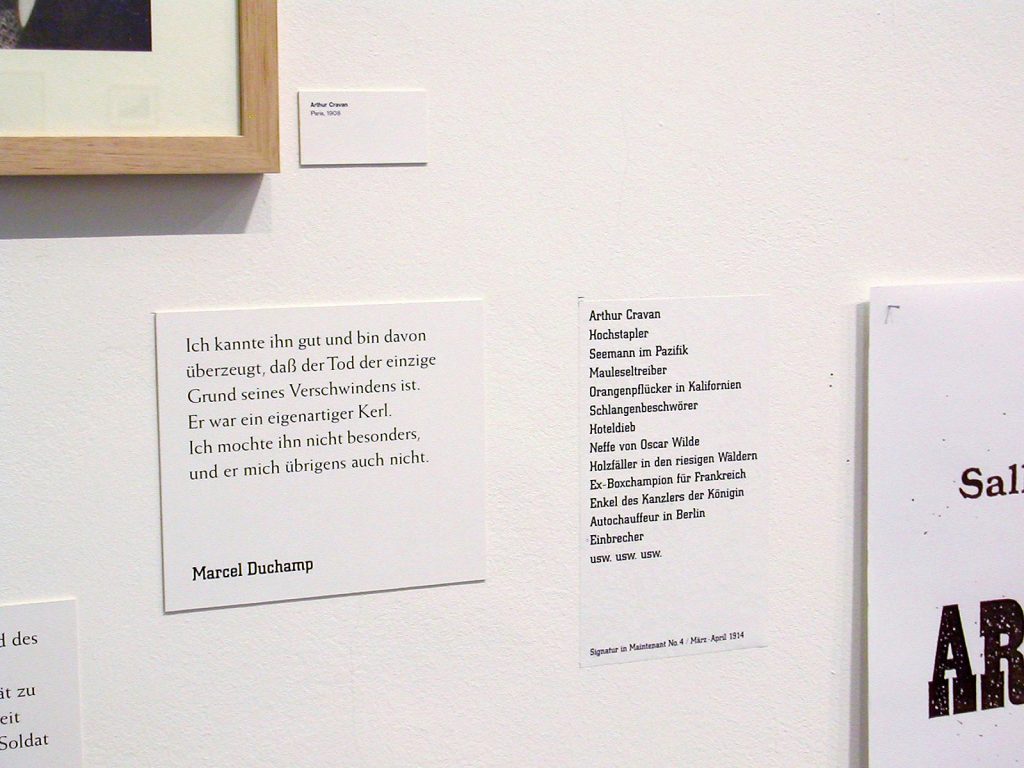

I am grateful for this revival of the original 2002 exhibition because it was an important project to me for reasons both private and methodological. Gestures of Disappearance was a curatorial narrative that operated largely without original works of art. I needed works on loan only for Chris Burden and a few pieces by Ader; much of the rest were photocopies and texts that were presented in typographic designs by the Leipzig-based graphic artist Till Gathmann. I obtained copies of Lee Lozano’s language pieces and notes from the archive maintained by her estate in New York and presented them as they were. In Barcelona I met Isaki Lacuesta, who was working on a documentary film about Arthur Cravan and had compiled valuable material. He gave me a shoebox full of photocopies that I used as sources for reproductions. We then arranged for a pre-premiere of Lacuesta’s film in conjunction with the exhibition in Leipzig. I received permission from Bas Jan Ader’s estate to make my own reproductions of several works and documents, and the exchange of letters with the estate and his widow, Mary Sue Ader, led to the discovery of film footage about Ader’s last project that had never been shown in public.

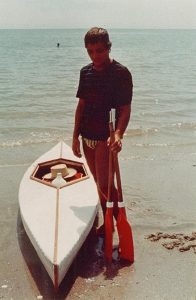

The exhibition cost very little to produce. Instead we spent our time and the local production resources on developing a narrative about disappearance based on the calibrated alignment of different gestures of showing that left no doubt about their theatrical character. We used original works only when it made good sense in light of their status; in most cases they were dispensable. Gestures of Disappearance spoke with a curatorial narrator’s voice that projected a literary form into the gallery rather than arranging pieces of art. Despite the formally austere mise-en-scène, it was a melancholy text that spread out over the four walls and tied its protagonists together with a recurrent metaphor, a sort of chorus: the image of the ocean passage, of being at adrift and at the mercy of the elements, of putting out to sea and arriving nowhere.

Â

Arthur Cravan had noted that “the first condition for an artist is to be able to swim.” This swipe at his fellow artists appeared in large letters on one wall, and in the exhibition it took on an existentialist edge. Cravan presumably drowned in 1918 trying to escape across the Gulf of Mexico and on to Buenos Aires in a sailboat. In 1975, Bas Jan Ader set sail to cross the Atlantic as part of his project “In Search of the Miraculous” and disappeared without a trace; only the tiny boat was found some time later. And in 1973, Chris Burden took a canoe out into the Gulf of Mexico, where he spent eleven days utterly by himself. These stories, images, and male myths—because that is what they are—do not make for good legend. The three men’s lives, like Lozano’s self-dramatizations, reveal them as victims rather than heroes. That is why the artists of the generations that followed saw very little in them that they could build upon. These four mark endpoints—tragic discontinued models of an outworn vision of art and the artist’s role they were so passionately committed to that, in bidding farewell, they gave it final form.

Alexander Koch